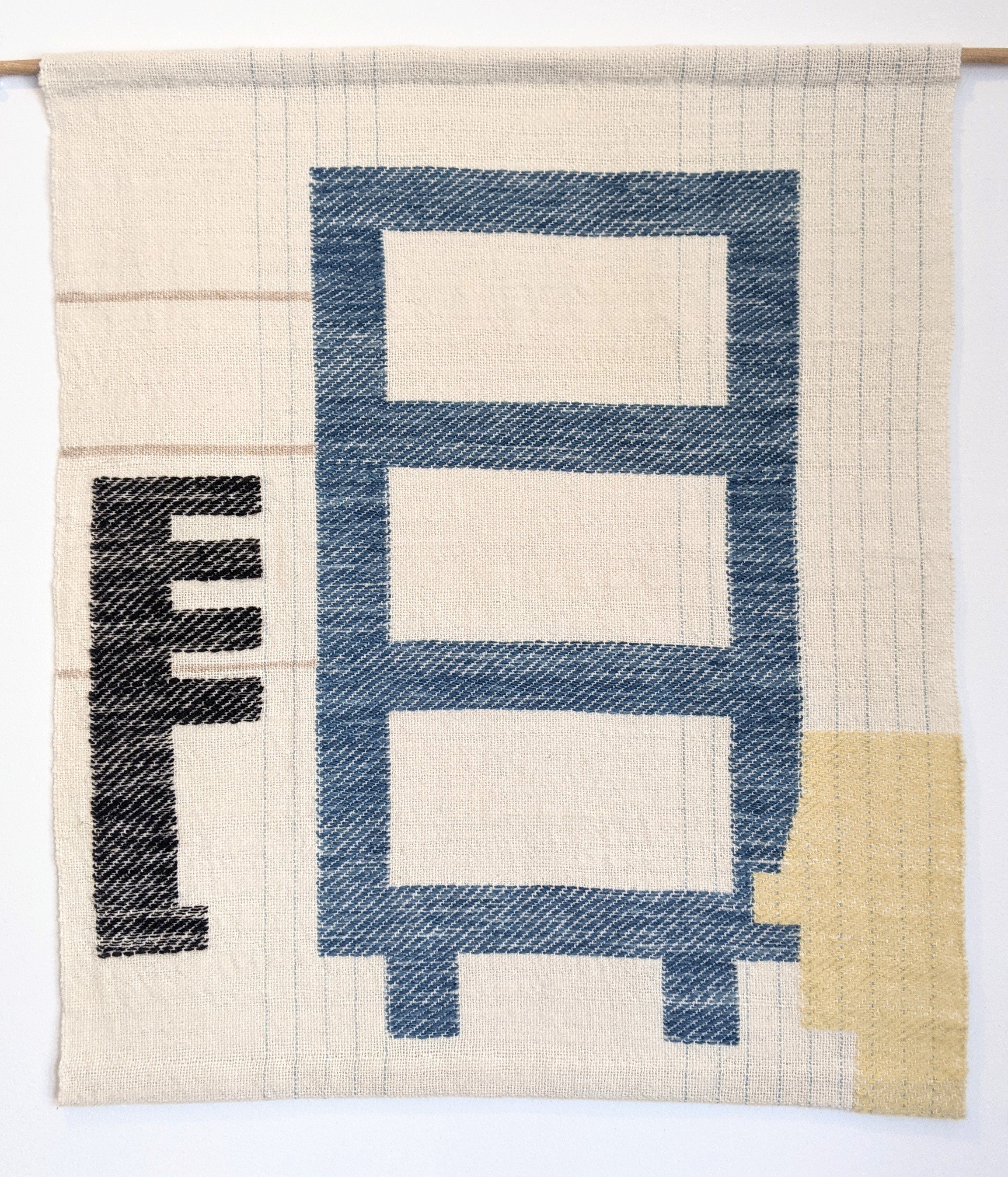

Writing about tapestry yesterday led me to thinking about how infrequently I work with forms that have no functional utility. I feel like it’s an old standard, a greatest hit—the functional versus non-functional in craft (and the ways this is and isn’t different from discussions about form and aesthetics that happen in fine art circles.) I do get something new each time I play it through. The pandemic has resulted in my dipping my toes deeper into the world of straight-up art objects. I can see the appeal and maybe one day I’ll loosen up and unabashedly make art objects for the sake of beauty, but I‘ll admit, I’m pretty damn ambivalent about the prospect.

Because tapestry takes so long to weave, I began making small paintings to explore proportion, play with color blending before committing a design to the loom. Frugal curmudgeon that I am, I also wanted to explore whether or not I even enjoyed painting before deciding to jump into making lake pigment paints out of the remains of my exhausted dye baths. To my surprise, several of the small paintings sold and a gallery inquired about exhibiting them, so I kept on with it. Despite this, my conceptual footing technique is situated first and foremost within a craft vernacular. I have a deep appreciation for beauty in the world. I’m distracted by it and often have to stay focused to not get drawn off course by some glint of light on a wall. That said, I have a hard time with objects that are made to be precious. I appreciate the lifespan and lifecycle of objects I make. I like that they change, that they will eventually fade, even like that they break.

I don’t know if the attribution is to the originator of the phrase, but in his book about Buddhist psychology, Jack Kornfield recounts his teacher Ajahn Chah appreciating a beautiful intact teacup and saying “the cup is already broken.” We use handmade porcelain pottery in our house, always have, including making cups available for any children that visit. When something breaks, as it did this week—a white bowl with a grey and black stripe, dropped into the sink—we all know the call and response: “It’s okay, she can make another,” to which the response is “the cup was already broken!” We don’t hang around juggling porcelain cups or intentionally putting them in harms way, but I think there’s something strange about an object born to be a little too dear. Ditto for one that has no intended destiny or mission in the world. I’m more comfortable with objects that have the unfulfillable or anti-mission than I am objects that exist only in terms of their aesthetic properties. Like I said, a curmudgeon, a real stick in the mud, so this project at the Everson Museum really caught my eye: “Ceramics Collector Louise Rosenfield Donated 3,000 Pieces to a Museum with One Caveat—the Works Must Be Used.” That’s my kind of gal.

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

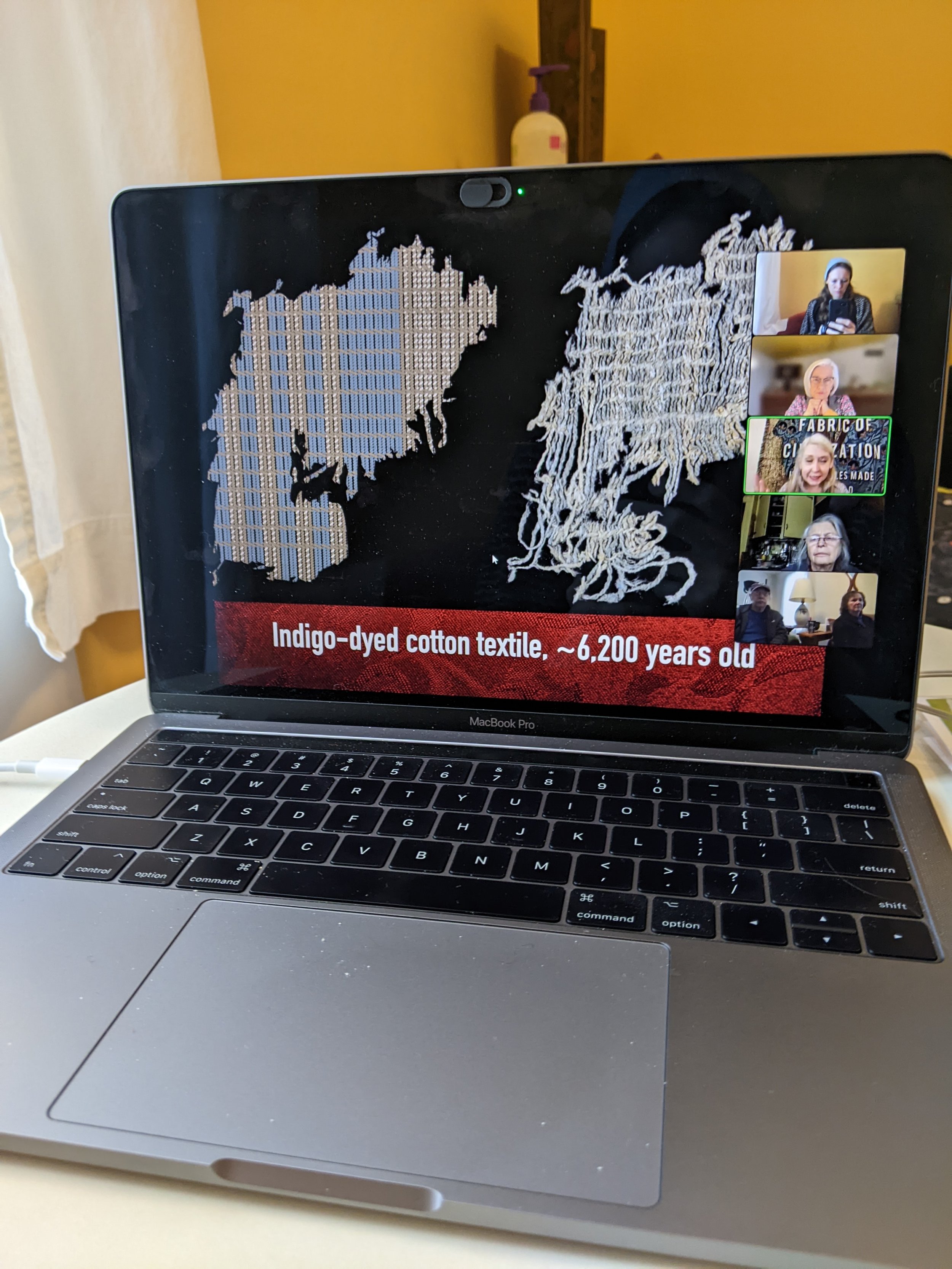

Not exactly related, but not unrelated either, today is the two-year anniversary of the first schoolday cancelled by covid. March 15th, the school closures were announced. March 16 was our first day of the New Now. I don’t remember that much, other than everyone in our household gathering in the kitchen to scream together. We howled a big, long NOOOOOOOOOOOO, holding the knowledge that it was a necessary harm-reduction strategy. I looked back at my photos from the day and this was the only one I had taken. It was to send to my parents, along with a text that said something like “I realize that you’re used to being able to just run out to the store and get more mayo for your sandwich, but please consider that this is a big deal and don’t catch an unknown virus on account of a ham sandwich.”