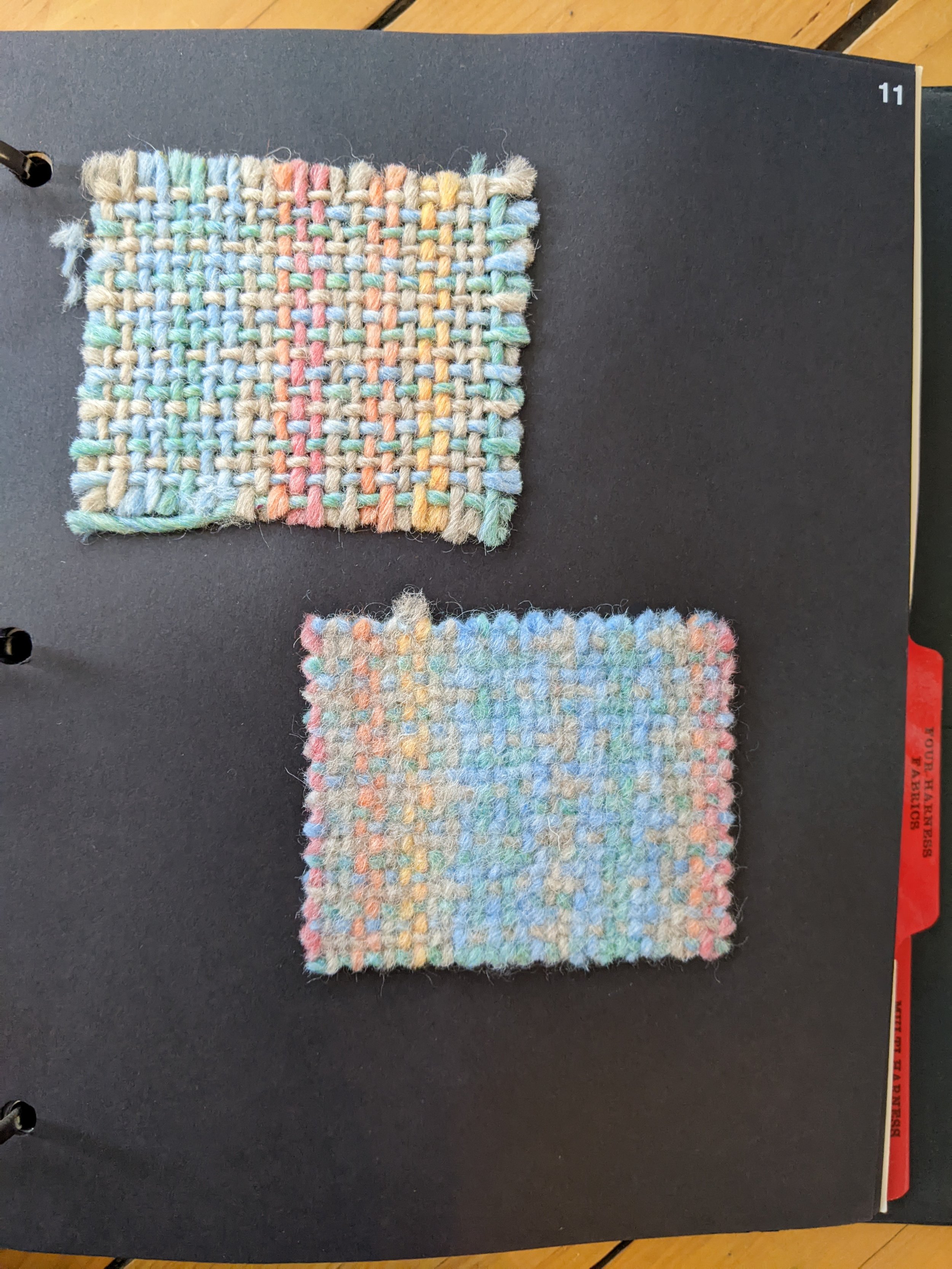

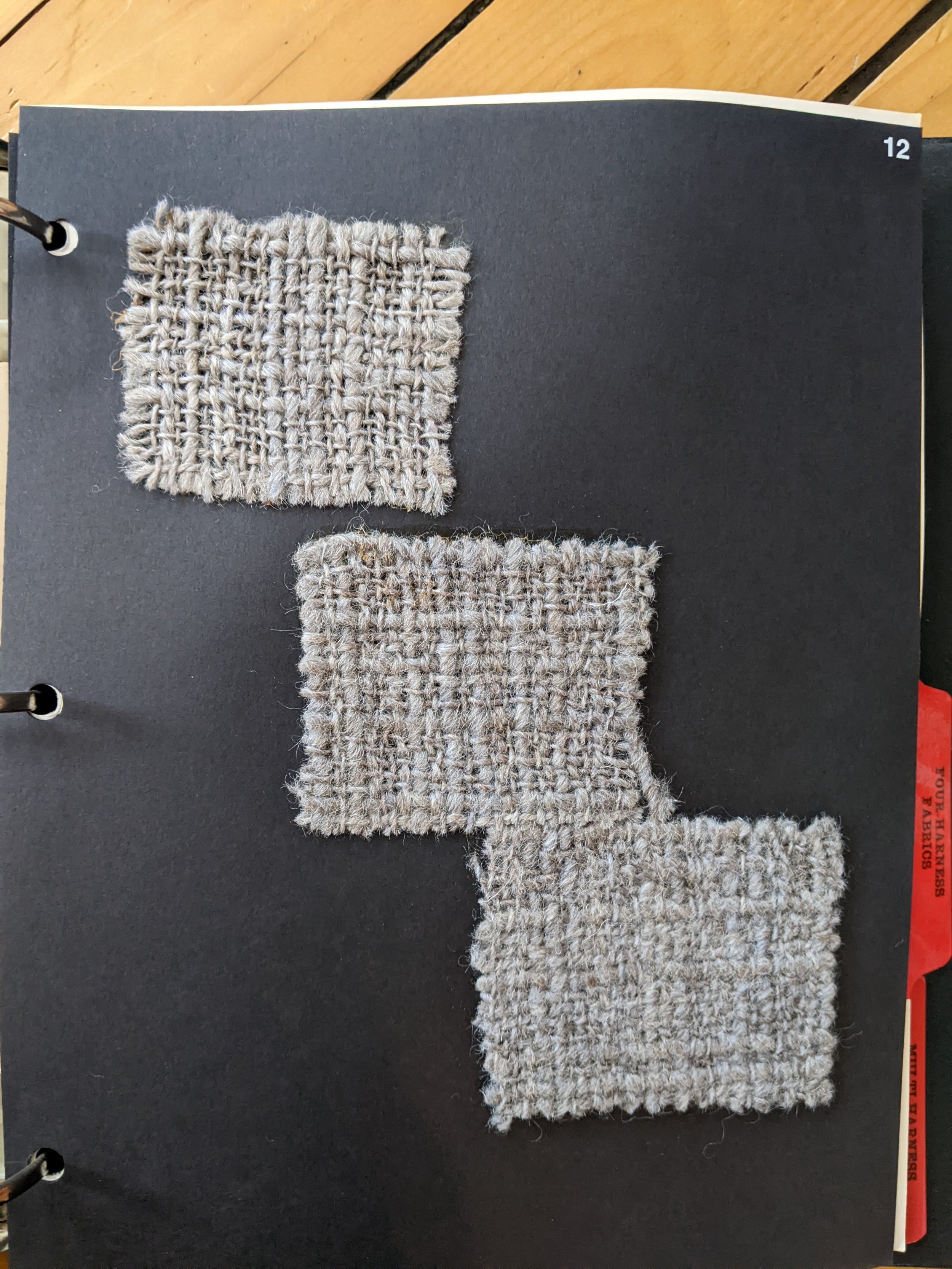

Just like a potter has to wait until after the final glaze kiln is fired to assess any cup they make, a weaver has to wait until cloth is off the loom and washed to evaluate its successes or shortcomings. This is called ‘fulling.’ Because the loom holds the threads under tension length and width-wise, the cloth initially presents itself as tidy, flat and orderly. The weft threads sit above or below the warp threads and retain their basic definition and structure. Their fibers are not interlocked with each other; the woven cloth resembles a gauze. At this point, the woven, unfulled cloth that sits on the loom is called ‘greycloth.’ This name probably dates back to pre-industrial homes or weaving shops, when cloth would accumulate all kinds of household soot, dirt and dust on it before being washed and prepared for use or sale. White or neutral colored cloth would certainly appear grey or dingy, after being in a space with poor ventilation, in close proximity to a fireplace hearth or being touched by hands that were also involved in other domestic or agricultural pursuits. The final step in finishing a piece of woven cloth is to soak, wash and agitate it, which causes the yarns to expand—this expansion is called the yarn’s ‘bloom.’ When the yarn blooms, its fibers interlock with the fibers of other strands, making the cloth denser and changing its appearance—sometimes substantially. Here are some before-and-after fabric samples created by the weavers at Harrisville Designs in NH, followed by some close-ups of the fabric I’m weaving. The woven samples are on the top, swatched of the completed fulled cloth are on the middle and bottom, demonstrating the effects of different levels of agitation.

Wool takes very little encouragement to bloom, just a water and hand-agitation. I like my blankets to retain some of their initial ‘gauzy’ definition, so you can still distinguish between weft and warp threads. This might not make for the warmest blanket, though. In the first sample above, you can see that the finished swatch on the bottom has become very dense, the fibers are well interlocked and the any visible space between the yarns is gone. To create a dense woolen blanket, modern weavers use the agitation of their washing machines. Preindustrial weavers didn’t have this luxury and the cloth was agitated or beaten by hand. In a process called waulking, weavers sit in a circle, beat the gathered cloth against a hard surface and pass along to their neighbor, often aided by worksongs. Below is a short video of Norman Kennedy of the Marshfield School of Weaving waulking with a group of students, posted by Thistle Hill Weavers, the mill and studio of textile historian Rabbit Goody in NY.