Bet you’re getting anxious to see me start weaving. I am too. Weaving at the loom is one of the singularly most absorbing, peaceful, pleasurable experiences I have in my life. It just takes a heck of a lot of other steps to get there—especially if I’m working with handspun and have committed to showing folks the process start to finish. Typically, there are 3 or 4 projects at work at any one time in the studio, not to mention work in clay happening in parallel. Upside to all this wool work—I think we’ll actually have enough yarn done this week to complete two blankets together!

I did a little extra spinning because I attended two fantastic online events—a conference sponsored by MOMA composed of artists coming together to discuss the work of Sophie Tauber-Arp and a lecture by Virgina Postrel on her book The Fabric of Civilization. Postrel mentioned those Viking ships in her talk too. She compiled research on available tools and spinner output in an 8 hours period to peg time it would take to spin enough for a Viking sail at 385 days. (That’s not counting the weaving and dying.) Making the sail, she noted, would take far, far longer than the building of the ship itself.

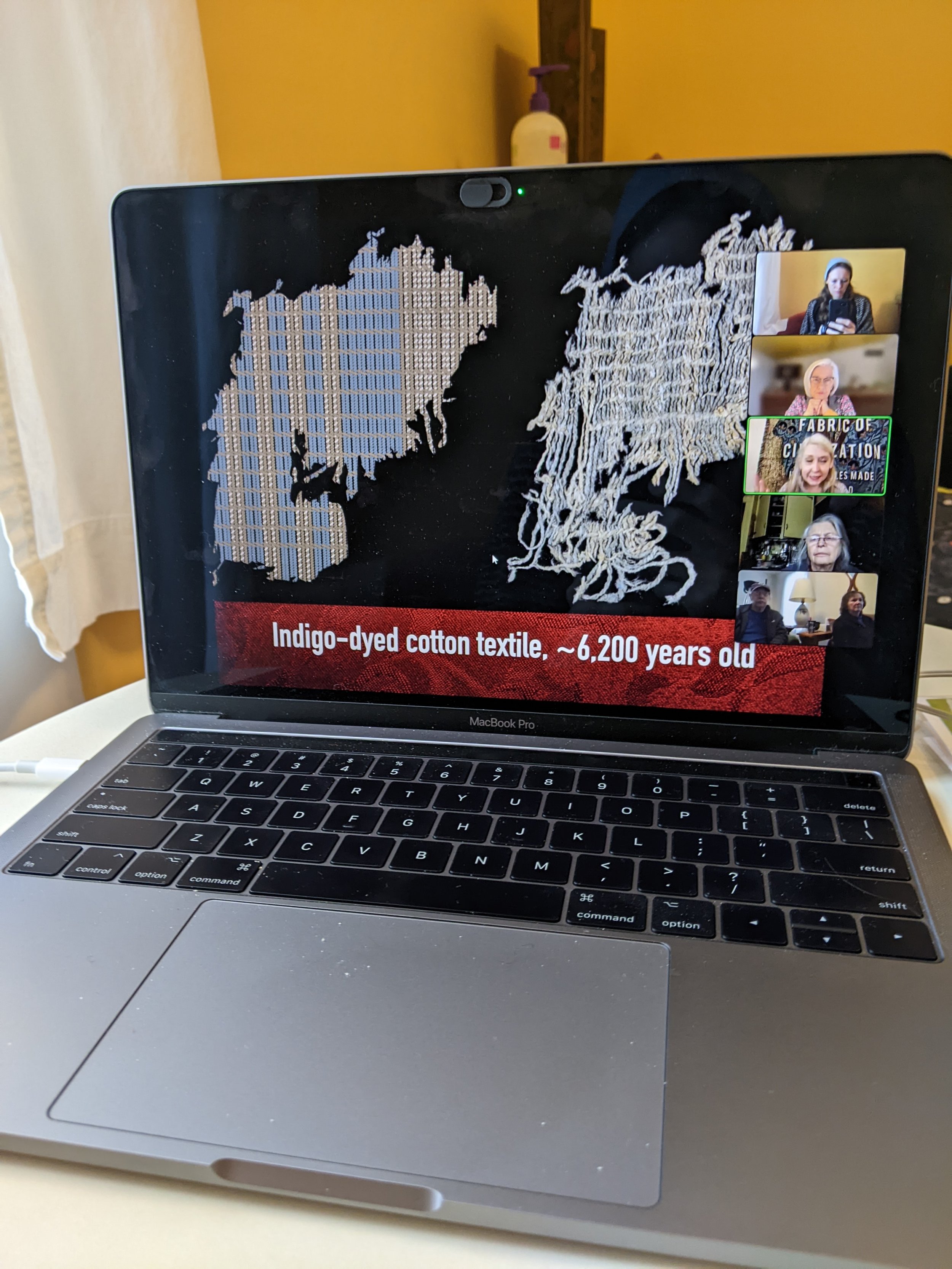

At the Arp conference, curator Anne Umland invited triads of artists/writers to view the MOMA exhibition, share some thoughts or responses to Arp’s work and then begin to ask each other questions. The first screen above shows fiber artist Sheila Hicks and architect/artist Amanda Williams discussing the work of Sophie Tauber Arp. The second screen shows Virginia Postrel’s slide of a scrap of indigo-dyed textile next to a computer-generated grid illustrating the composition of the weave.

The last pairing of the conference were dancer/collaborators Rashaun Mitchell and Silas Riener in conversation with Mexican artist Pia Camil. Camil is an artist fascinated with Modernism’s promises and failures. She noted that within Arp’s modernism, she utilized motifs, colorblocking or visual composition that Camil recognized within Mexican folk art, historical architecture and the design of historical public spaces in Mexico City. Renier and Mitchell’s contribution was a four-minute dance composition based on the motifs in Arp’s painted compositions. The three agreed that Arp’s aesthetic and applied arts techniques had many antecedents; they weren’t born solely of her psyche. She was in an artistic lineage that was broader than her training. In making work based on hers, they, in turn, claimed her as an aesthetic ancestor. Mitchell described the pair’s film as “entering into a ghost dialogue with Sophie.”The three were in consensus that an artist never strives for new creative work without precedent—such a challenge was folly.

87 year-old Hicks, at this point, chimed in from her studio in Paris to note that the longer she lives and works the more convinced she is that all art is call and response and iterative repetition is the state of creative inspiration, even across generations of makers who are strangers to each other. Reiner agreed, “we are standing in the river of time together.” I love that image. I often use basic structures/shapes in my work and utilize labor-intensive processes to make pieces that appear (sneakily) uncomplicated until one explores the making up-close. I find it a solace that every shape and structure has already been woven and that when I spin, weave or feed my indigo vat some fructose, I’m participating in a relationship between plants and animals that goes back as far back in human history as archeologists go. Starting from the knowledge that everything has already been made before in some form or another, what’s left is the freedom to decide what tributary of that “river of time” you’ll slip into next. How delightful.